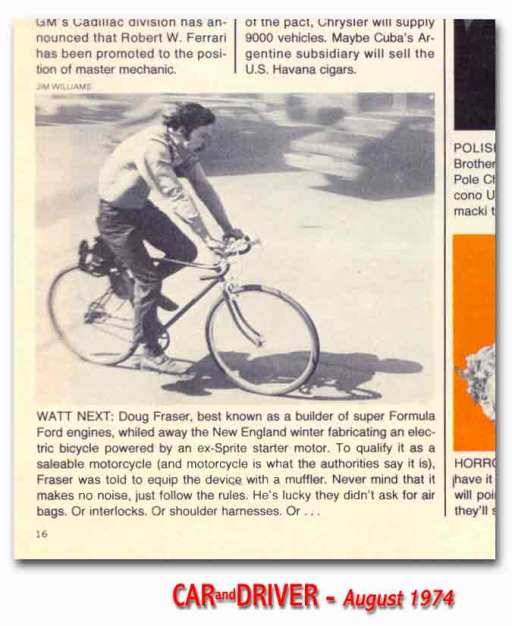

(All photos by Doug Fraser — Unless I’m in them.)

Crandall-Hicks

I’d been training monkeys as a lab technician at Arthur D. Little in Cambridge Massachusetts when Vietnam flared up. As a result, my project lost its funding and I lost my job.

At about this time however, Crandall-Hicks, (the U.S. importer of BMC cars) was in the process of not negotiating with their line mechanics, causing them to walk out en-masse. I never found out what the issue was, but I needed a job and at that point, Crandall-Hicks was prepared to hire anyone who knew that turning a bolt clockwise usually made it tighter.

This turned out to be a great opportunity to play with interesting cars. BMC had a racing department with lots of performance goodies (This was the BMC special equipment list), and as employees, we received discounts on parts.

While at Crandall-Hicks, I built a full-race Sprite and even hopped up (don’t laugh) and autocrossed an MG 1100.

Autodynamics

I’d been at Crandall-Hicks a few years when a company in Marblehead, Massachusetts, called Autodynamics advertised for a racing engine builder. Early Autodynamics Publicity

See: http://autodynamics-reunion.com

I applied for the job and then pestered them mercilessly until they agreed to hire me.

I started as an apprentice to John Harkness, master Formula Vee engine builder. Under his tutelage, I learned to build some pretty strong Vee engines but, more importantly, I spent a lot of time on the dynamometer.

These were pre-OSHA days. The dyno sat about 6 feet from the plywood wall against which the dyno controls were situated. I stood with my back about a foot from the dyno – engine screaming – working the throttle with my left hand, the load control with my right, reading the tach with my left eye-ball and the torque meter with my right, and somehow managing to write down some numbers. (OK, I’m kidding about the eye-ball thing). I’m glad I never blew up an engine; I wouldn’t be here now.

Formula Ford

It was early 1969. Formula Ford was in its first year as an official SCCA class, and Autodynamics decided to enter the fray.

l remember Autodynamics president Ray Caldwell calling me into his office and asking if I thought I could build a competitive Formula Ford engine from scratch. “Sure,” (I lied.)

I ended up building an average of two engines a week for the Autodynamics Caldwell D-9 Formula Fords and dyno testing every one of them.

Skip Barber

As an engine builder, I got my biggest break when Autodynamics brought on Skip Barber to drive the D-9. Skip was one of the best racing drivers in the country and, as long as I didn’t handicap him, my engines were going to look great.

Racing drivers are, with some exceptions, an odd lot. If they win, it’s their driving, if they lose, it’s because the other guy had a stronger engine.

Skip won regularly, so there were a lot of folks wanting engines just like his. He once quipped that if he showed up with a whirling propeller on the top of his helmet, next time out, everyone would have them.

Skip was a smooth and consistent driver, sensitive to small changes and able to report, in an understandable way, how an engine was running. This was helpful for fine-tuning his engines at the track.

Ultimately, Skip won the 1969 SCCA National Championship.

There is a great story about this win in the Boston Globe.

Doug Fraser Racing Engines

Autodynamics had been selling lots of cars and winning lots of races but not making much money. In 1971 they filed for bankruptcy.

I took a day job as a service writer at a Rolls Royce dealership in Boston.

At the time, Bill Alsup, a top F/F driver from Woodstock, Vermont, had two Ford engines at Autodynamics for rebuilds. He offered to pay me in advance if I’d take them home and finish them so I began building engines during evenings and weekends. This was the start of Doug Fraser Racing Engines.

In the meantime, Skip Barber had started the 1970 season with a free ride from Techno and engines from Holman-Moody. However, the engines didn’t work well.

Holman-Moody was the builder of some of the world’s best large displacement engines, but they hadn’t yet mastered the painstaking techniques for extracting those last few horses from a small engine, and Skip couldn’t wait. So, he hired me away from my service writer job (I wouldn’t have lasted there much longer anyway), borrowed the engine dyno from Ray Caldwell, and set me up in a garage complex in Brookline, Massachusetts.

The F/F field was getting much larger, several new engine builders had entered the scene, and it was becoming a serious industry.

I realized that the old two-hand, two-eyeball method wasn’t going to suffice any more, so I drew on some of the nerd-skills I’d learned as a lab technician, and instrumented the dyno. It was primitive but worked. I used a surplus Leeds & Northrup X-Y plotter that weighed about 150 lb., a torque transducer, and an RPM pickup.

Now I could run a baseline test, make a change, and run a second test, while plotting right on top of the previous line. It became obvious when something did or did not work.

(This is one of the plots from Skip’s 1970 engine)

One of my more clever tweaks was machining the timing cover to fit a paint can lid and slotting the timing gear. This allowed me to make cam timing changes in a matter of minutes so that other factors (engine temp. etc.) were less likely to affect the test.

Once again, Skip Barber won the SCCA F/F National Championship. (He also won the Formula B National Championship that year.)

DFRE Gets Serious

Business was picking up, forcing me to move out of my basement. I found an excellent location on Beringer Way in Marblehead.

I purchased the Stuska water brake dynamometer from Autodynamics, and outfitted the shop with a crankshaft balancer, magnaflux equipment, air flow bench and other necessary equipment. Then we produced a catalog:

DFRE Gets Not-so Serious

Autodynamics Reorganizes

Autodynamics reorganized under Chapter 11 and got back to building Formula Fords as well as a new Formula Vee, the D-13.

Original Concept Sketch of the D-13 by Bill Woodhead (who, in my opinion, was one of the most creative people on the planet.)

1973 Autodynamics Catalog (F/F and F/Vee pages)

Reeves Callaway and his Caldwell D-13 at speed (Prior to building his 200+ mph Callaway Corvettes)

David Loring

Another top driver running the D-9 Formula Ford was David Loring. When he first started racing, the SCCA said he was too young to get a competition license, so he went out and won everything else instead.

An excellent article on David Loring by Gordon Kirby.

David Loring passed away on September 19, 2012.

Obituary

U.S. Formula Ford Championship 1972

In 1972 the International Formula Ford Championships were scheduled to be run at Brands Hatch, England on October 29th.

Because the ARRC runoffs would not occur in time to determine who would represent the United States, a Formula Ford Championship race was held in September at Mid-America raceway in Wentzville Missouri.

This was an invitational event with the current front-running F/F drivers from each SCCA division invited as well as all the top National finishers from 1971.

The winner would receive an all expense paid trip to England.

Twenty-four cars started the event; seven were running Doug Fraser engines.

This is from the Competition Press & Autoweek article about the event:

Baldwin Heads for England –

The U.S. has a F/F Champ.…the nods seemed to go to anyone running a Doug Fraser engine ̶ predictions which later proved more accurate. Three of the top 4 qualifiers and 4 of the top 5 finishers were running with the ‘dfre’ decal.

“The Fraser engines are superior to anything we run here,” [Gordon] Smiley said.

[Ron] Dykes, also with a Fraser, said that in England the Scholar is probably the top engine, “but the Fraser is every bit as competitive”.

If the Fraser is the stand-out engine in America it could be well that the top 3 Yanks have them since they will face enough disadvantages when they get to the world title bash.”

Competition Press & Autoweek, Oct 14, 1972:

Car&Driver IMSA Pinto

In the mid-1970s I was approached by Pat Bedard from Car & Driver (C&D) magazine to build engines for their latest project car, the just-released 2.3 liter Pinto to be raced in the IMSA sedan series.

This was a great challenge, and being the first one to develop this engine for racing was pretty exciting.

Ford provided me with the SAE paper describing the 2.3 engine development as well as considerable technical support.

One area that most affected the power of the Pinto engine was reworking the head and inlet manifold. These are the original flow bench plots from that engine.

Turbochargers

On the way back from accompanying the C&D Pinto to Daytona, I was introduced to a new C&D project car, the turbocharged Opel. I’d never ridden in anything so fast. Or perhaps it was the insane driving in the canyons of New York City. Either way, I was hooked.

At this point, we shifted our emphasis from race car engines to custom turbocharger installations and began manufacturing kits for Porsche 911s and BMW 2002s.

The major lesson I took away from all this was that I was pretty good at developing and building high performance engines, but I was lousy at making money.

We closed down DFRE in 1976 — while there were still just enough salable assets to cover most of the outstanding debts, and began collecting monthly paychecks.

I was initially hired as a technician by Creare, Inc in Hanover NH – a high-tech research and development company. However when an opportunity opened up at the Thayer School of Engineering at Dartmouth, I jumped on it.

After 37 years at Dartmouth, I finally retired with Emeritus status.

However, being completely incapable of keeping my hands away from high performance engines, I have equipped my home workshop with an engine dynamometer, various machine tools, engine balancing equipment, etc. and still manage to spend a good amount of time tinkering.